Posted on Oct 31, 2017 in

COLLEGE DAZE

By Kassidi McKayla Kaminski

Kassidi McKayla Kaminski is a sophomore studying Psychology in the Liberal Arts Honors Program at The University of Texas at Austin. After graduation she hopes to attend law school and is currently a member of Delta Gamma and a Young Life leader at Reagan High School.

Kassidi McKayla Kaminski is a sophomore studying Psychology in the Liberal Arts Honors Program at The University of Texas at Austin. After graduation she hopes to attend law school and is currently a member of Delta Gamma and a Young Life leader at Reagan High School.

I’m a crier. I cry when I see a puppy, when I hear Kelly Clarkson’s Breakaway, and when I remember that Jonathan Groff (one of my favorite actors) is extremely unattainable. My mom has remarked that I cry too much, and oftentimes over trivial matters. But those trivial matters – the little things in life that break the routine of the mundane – are what excite me the most. It’s the nostalgia I feel when the sun touches the trees in a perfect way, or the freedom I sense when Michael hits the key change in Man in the Mirror. Truthfully, our whole lives are defined by a good key change – the sudden switch from our present, everyday tempos to a beat that lifts us to new heights and questions our range and abilities.

The playground of the Cherokee Boys and Girls Club has the Smoky Mountains as a backdrop – definitely not something you see in Missouri City.

One of my biggest key changes occurred at the hands of some very special second graders. When I met these kids, I was a seventeen-year-old high school junior with a lot of harbored anxieties. I was battling a serious illness at the time – one that proved to be near-fatal. But I had insisted on attending my school’s mission trip to a small Cherokee reservation in North Carolina. I couldn’t have foreseen the impact those seven days would have on my life. After all, mission work is supposed to be about the people you’re helping, right? But God has quite the sense of humor.

Because Native American reservations exercise tribal sovereignty, they’re technically separated from the rest of the United States. In some parts of Cherokee, the poverty resembled that of a less developed nation, a poverty which I had never before experienced firsthand. My Houston suburb wasn’t the nicest one around, but it did little to prepare me for the deprivation sitting in the middle of America.

One of our first stops in Cherokee was the Boys and Girls Club, or the CYC. The building looked like a remodeled elderly care facility, but I use the word “remodeled” tentatively. The front doors opened to a dimly lit cafeteria with paint chipping off the walls. The poverty was almost tangible, and the people who greeted us all shared a warm smile masqueraded by a gentle sadness. They showered us with such enthusiasm that I felt like a celebrity instead of an average teenager from Texas. They led my best friends, Georgia and Caroline, and myself into a humble, unadorned classroom bustling with the chatter of little second graders. Our job was quite simple: have fun with them. Help them with their math homework, read them a short story, play Connect Four, and just let them forget.

“Forget?” I had asked myself. “Forget about what?”

I met Esiah first. Esiah was big for a second grader: meaty hands, tall stature, relatively lower voice. The perfect giant teddy bear. Esiah loved Legos, especially ones about Star Wars.

“Do you play Legos with your siblings?” I asked him.

“Sometimes. I have a lot, you know. Like five.”

“Wow! That is a lot! Your mom must be a very busy lady.”

“Probably. That must be why I don’t see her anymore. She’s an alcoholic and was getting rehab in South Carolina, but she ran away, so the cops are after her now.” Esiah didn’t skip a beat. “My grandmas, I live with them, you see, they say she might be looking for my pap. But he’s in jail for pulling a gun on somebody. Do you want the blue lightsaber or the red one?”

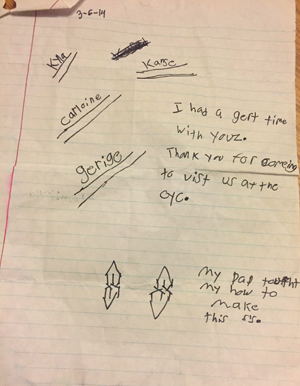

The note Kyla wrote for Georgia, Caroline and me. I keep it taped to my bathroom mirror.

I couldn’t hide the look of complete shock on my face. What eight-year-old Esiah considered normalcy, I labeled unimaginable. He told me his life story with such an air of casualness that should have been foreign to a child. I finished playing Legos with Esiah and moved on to the other kids, sick with the inevitability of more heart-wrenching stories.

A horrific theme of abandonment and neglect clung to each child I met like an unrelenting shadow. When Mary told me that her father was in the hospital on life support, Mary’s teacher prompted her to tell me what he had done. With surprisingly mature vernacular, she calmly explained, “Daddy overdosed. That’s when you take too many pills, like this, and they make you real sick and sleepy.” She tilted her head back and pretended to tap the contents of a pill bottle into her little mouth. Mary was seven.

Kyla loved spending time with her dad, especially since her mom was usually sleeping after a rough night of drinking. Her pap taught her how to draw “Superman S’s,” a trick to keep Kyla distracted whenever her mom went on a drunken rampage. Kyla was eight.

Jenna was the beauty queen of the group, idolized by the entire town after her title win in the local Little Miss Cherokee beauty pageant. But Jenna’s doll-like eyes swam with overused tears when she told me that her daddy had just moved far away and that she wasn’t allowed to see her mommy. No one would tell her why. And Jenna wasn’t supposed to cry, because she was Little Miss Cherokee. But Jenna was only seven.

I beaded friendship bracelets in the craft room with Little Hawk, who grabbed me around the knees and begged me not to go, making me promise that I would return to him, that I wouldn’t ever leave him. Hawk didn’t understand why Texas had to be so far away from Cherokee. I didn’t want to say a forever goodbye. Hawk was eight.

Kyla giving me a high-five after rough game of freeze tag.

My composure crumbled as soon we left the Boys and Girls Club. I couldn’t stop the tears cascading down my face or the rage for the neglectful parents welling up inside of me. I jerked my eyes toward the sky and voiced my utter disbelief that God would let innocent children live like this. There I was, a spoiled, private school white girl who found room to complain about any misfortune. Every dilemma was a catastrophe to me, all seemingly bad days deemed unfair. But, I lived with both of my parents. Neither of them were alcoholics. Neither of them did drugs. I was blessed, yet unsatisfied. I was seventeen and the target of a humbled juxtaposition.

And like a glimpse into the eyes of God, a curtained opened, and I relived the day’s events and saw despair’s mortal enemy hard at work: joy.

Mary’s forced maturity dissolved away when we dressed her baby dolls together. She coordinated her outfits and showed me how to use the play kitchen. Mary thought not of her reckless father because she was seven, and seven-year-olds think about baby dolls.

Kyla handwrote me a note, shy but proud of the special S’s her pap taught her to draw. “Carloine, Kanse, and Gerige,” she addressed to my two best friends and me. “I had a gert time with youz. Thank you for coming to visit us at the CYC. My pap taught me how to make this s’s.” Her careless mother did not phase her. Kyla was eight and too busy spreading the thoughtfulness of handwritten sentiments.

Jenna beamed when I praised her cartwheels. She did them until she was exhausted and dizzy; her absent parents were not an issue. Jenna was a talented, outgoing, seven-year-old gymnast and beauty queen.

Little Hawk sprinted to the bead table to see how many necklaces he could fashion for me during art class, so I could wear them and always think of him. His teacher scolded him for running indoors and taking too many beads, but he returned to me with a sneaky smile, a pocketful of beaded contraband and a confident wink. His fear of abandonment was not allowed in this moment. Hawk was eight and needed to finish making necklaces.

Here’s me and my new friend pretending that math homework is as fun as Legos.

My friends in Cherokee were roughly 10 years younger than me and had more joy and wisdom than I could have claimed to share. I was seventeen, and I was beyond spoiled. I was selfish to exaggerate life’s daily annoyances into dramatic concerns.

And sadly, this is the mantra that too many of us follow. The inconvenience of spotty wi-fi or Starbucks messing up our order are so trivial in the grand scheme of, well, everything. When I left Cherokee, my attitude on life shifted in a key change so dramatic that it forced me to reevaluate my purpose on earth and understand how young children – born into the claws of abandonment, neglect, and pain – so quickly found the key to life’s joys.

Too many people place their happiness in big gestures or in monetary gain. But life, by definition, isn’t extravagant. It is, in fact, quite ordinary. Life itself is a culmination of ordinary, everyday events that fuel us to keep living. It’s making beaded necklaces for your friends, landing a perfect cartwheel or telling someone “thank you” in a handwritten note. These actions are not time-consuming or astonishing feats. They are simple, life-giving and ordinary.

The most extraordinary people are ordinary at heart. Their humility rejects the idea of fame and fortune and allows them to find joy in the little things. They have acknowledged what they can’t control in life and have siphoned it to spread positivity and joy in a world whose mindset definitely needs an adjustment. Like Michael pleas right before the key change in Man in the Mirror, “If you wanna make the world a better place, take a look at yourself and then make a change.” To me, those are the people who have found the key to life. And they use it better than most.

Kassidi McKayla Kaminski is a sophomore studying Psychology in the Liberal Arts Honors Program at The University of Texas at Austin. After graduation she hopes to attend law school and is currently a member of Delta Gamma and a Young Life leader at Reagan High School.

Kassidi McKayla Kaminski is a sophomore studying Psychology in the Liberal Arts Honors Program at The University of Texas at Austin. After graduation she hopes to attend law school and is currently a member of Delta Gamma and a Young Life leader at Reagan High School.